“Techlash” is a term that indicates a strong negative feeling in reaction to modern big technology companies. Such expression has been (also) used to frame the plethora of rules on digital technology recently adopted by various policymakers worldwide.

This term, however, does not allow us to appreciate that, in certain contexts, there are different varieties of techlash. Let’s take the United States: here, techlash means different things for different political actors. For Democrats, it means enhancing antitrust enforcement and data protection regulation. For Republicans, it means targeting “woke” content moderation and preserving “free speech”. This divergence of views, combined with the composition of Congress, has determined a “frozen landscape” in US tech regulation for years.

Of course, this is a simplification: there are examples of bipartisan efforts, and at the state level the positions can change. However, these differences are stable enough to indicate different “sets of ideas” employed by Democrats and Republicans about how regulators should (not) influence the development of certain technologies and industries.

The United States is often compared with the European Union, which has, on the contrary, been way more proactive in legislation. In my opinion, this was mainly determined by the fact that “techlash” ideas by dominant parties in EU institutions are not incompatible as in the American case. The idea of a “social market economy” drives all of the majority groups (S&D, EPP, Renew, Greens) and Commissioners through a mix of:

pro-competition attitude, with antitrust policy as one of the main pillars to foster the common market, and also as an attempt to rein Big Tech. See the Digital Markets Act;

a “social” component, meaning that regulation of markets should take into consideration “fairness” and human rights. See the General Data Protection Regulation and the Digital Services Act;

pro-harmonising attitude, that frames the “harmonisation” of the EU market as a positive aim in itself.

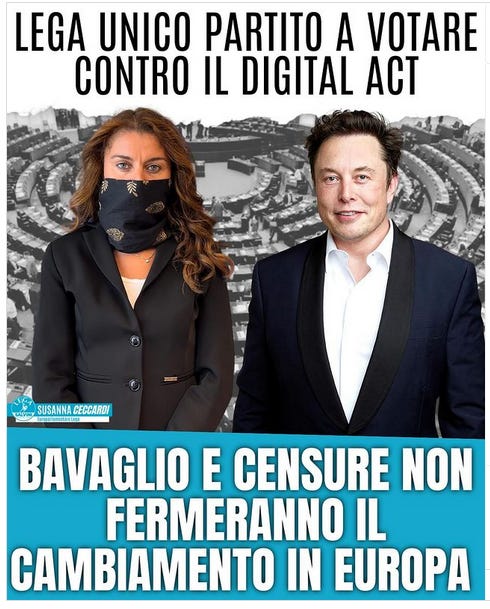

However, if the next European Parliament elections significantly strengthen right-wing parties, a different “variety of techlash” may become relevant in EU institutions, significantly impacting this consensus on technology policy. The bigger winners of the Elections might be the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) groups, which propose an alternative set of ideas:

the topic competition of policy is way less important: albeit often inconsistent, their conservatism is less sympathetic - if not hostile - to “activist” antitrust enforcement such as Vestager’s;

freedom of speech is way more relevant than fighting misinformation, which is framed as speech policing;

limiting overregulation is more important than EU “harmonisation” at all costs; moreover, increasing EU-level powers has to be avoided.

With key positions in the Council of EU occupied by right-wing parties (i.e., Italy and the Netherlands), my hypothesis is that in the next years, the EU may become more similar to the US, with incompatible varieties of techlash freezing the tech regulation landscape. Therefore, EU tech regulation will diminish not only for physiological reasons (need to “digest” all previous regulations), but also because contrasting ideas will become a stronger veto point to new laws.

Policymaking will stop, then? No. First, the implementation of the regulations adopted in the last years remains a huge chapter. Second, some Member States will keep taking initiatives on their own. Third, governing EU parties might converge on new ideas, making the different “varieties of techlash” compatible. An example may be Von Der Leyen's emphasis on increasing industrial capacity through public procurement.

Talking about a “model” of EU tech regulation is good for explanatory purposes, but hides the contingent political factors that have allowed its emergence in the last two Commissions’ mandates. With the new European Parliament elections, we need to take into account the divergent “varieties of techlash” to understand whether, in the next five years, the EU will still frame itself as the global digital uber-regulator.