The 'Privilege Effect': online aristocrats in walled gardens

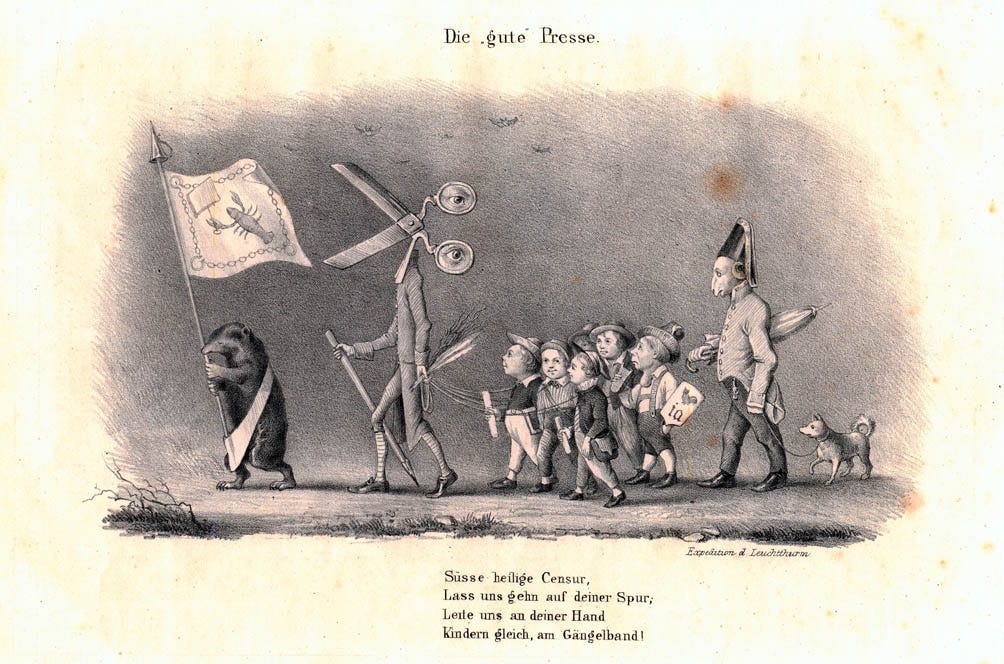

Why special status for old media institutions may not be a good idea

There is a clear trend in the recent EU activism on social media regulation: the construction of special, ad hoc privileges for “old media” institutions like newspapers.

Article 15 of the 2019 Copyright Directive provides press publishers with the right to claim revenues from online uses of their publications. Search engines and social networks are forced to sit at the table with press publishers and pay for a license for the mere fact of hosting content written by such publishers. This idea is wrong from many points of view: first, because newspapers are getting paid to have their content advertised; second, because it distorts the open web’s principle of universal hyperlinking. In many countries, these measures have failed spectacularly due to the tech companies’ boycotting. The EU market’s dimension seems significant enough to bring companies to the table, however, the long-term effects of the measure remain uncertain.

Article 22 of the Digital Services Act requires “Very Large Online Providers” and “Very Large Online Search Engines” to prioritise the content reports by “trusted flaggers”, that will be designated at the national level (Art. 19). By analysing the flaggers currently involved in the voluntary EU Code of Practice in Disinformation, many of them are “fact checking” and “source-rating” organisations, whose are often funded and managed by… newspapers and journalists. This is not a problem in itself, but the endorsement of these flaggers by mandatory regulation gives newspapers a privileged position to monitor content on social media.

Article 17 of the draft of the European Media Freedom Act proposes to introduce a special treatment for the content posted by media outlets. “Very large online platforms” have to inform media publishers, and wait 24 hours for answers, before their content is taken down or restricted. This obviously goes against the goal of “fighting disinformation”, especially if the final version of the law will confirm that publishers would access the special category through… a self-declaration!

In all these cases, the word “privilege” seems fitting: media outlets are increasingly considered a category with special powers and protection. Of course, some kind of special treatment (like in the case of politicians) has always existed and is driven by behind-the-curtains politics. However, the increasingly formalised nature of these entitlements makes the exercise of power by these actors way easier.

There are at least three reasons to be sceptical of these developments.

First, this process is (rhetorically) based on the assumption that “old media” is necessarily better than “social media”. However, this is increasingly discredited by research: for instance, social media are exposing users to more diverse opinions than traditional media, while the effects of fake news on society are likely very small. AI will not probably change anything.

Second, these measures seem to privilege “big” old media, and not the bankrupt local newspapers that are often described to support protection for mainstream media. For instance, the Spanish mandatory licensing law caused a Google boycott that was a disaster for small publishers. The Australian version of this law mainly channelled money from Google and Facebook to the Murdoch family. Is this the type of redistribution we want?

Third, this trend can further exacerbate the power centralisation by a few internet companies. We can define the “privilege effect” as the principle according to which the value perceived by an user when using a service derives from the privileges that such user has.1 The more privileges newspapers possess in walled gardens, the less they will be incentivised in switching to services where they would not have the same benefits. Why should they abandon big (and regulated) platforms to create profiles on Mastodon, where they are just considered “normal” users?2

Privilege effects are a particular case of a broader approach. According to Cory Doctorow, much of the current regulation of big tech companies further entrenches their power, because it assumes their dominance as immutable: “the ‘solutions’ on the table today require Big Tech to stay big because only the very largest companies can afford to implement the systems these laws demand.” Policymakers should remember that every institutionalisation of newspapers’ aristocracy in the social environment is likely to further centralise the power of both “old media” and “Big Tech” platforms.3

Clearly, this is inspired by the literature on network effects. In economics, the “network effects” is the principle according to which when more people use a product or service, its value increases. For users, network effects raise the cost of switching service, because such a choice lead to losing the possibility to interact with other users.

Old media news indeed constitutes only a minority of content on social media. However, newspapers are crucial to attract users, institute the “legitimacy” (or “coolness”) of services (like in the case of ExTwitter) and are powerful political actors.

In addition to centralisation, it might also lead to collusion. If a newspaper obtains privileges and checks from a social network owner, the incentives to hold that owner accountable decrease.